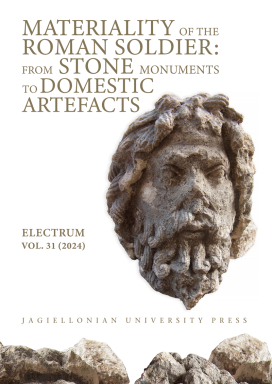

New volume

Religious Life in Ancient Cities, ELECTRUM, 2023, Volume 30. Published online 26 June 2023

see moreReligious Life in Ancient Cities, ELECTRUM, 2023, Volume 30. Published online 26 June 2023

see more

Journal publishes scholarly papers embodying studies in history and culture of Greece, Rome and Near East from the beginning of the First Millennium BC to about AD 400. Contributions are written in English, German, French and Italian. The journal publishes scientific articles and books reviews.

About the journal

Journal of Ancient History

Description

Electrum has been published since 1997 by the Department of Ancient History at the Jagiellonian University in Cracow as a collection of papers and monographs. In 2010 it starts as journal with one issue per year.

Journal publishes scholarly papers embodying studies in history and culture of Greece, Rome and Near East from the beginning of the First Millennium BC to about AD 400. Contributions are written in English, German, French and Italian. The journal publishes scientific articles and books reviews.

ISSN: 1897-3426

eISSN: 2084-3909

MNiSW points: 100

UIC ID: 486190

DOI: 10.4467/20800909EL

Editorial team

Affiliation

Jagiellonian University in Kraków

Publication date: 17.05.2024

Editor-in-Chief: Edward Dąbrowa

Cover Design: Barbara Widłak.

Cover photography: The head of the statue of Serapis (photo by M. Bărbulescu)

The work was supported by a grant of the Romanian Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization, CNCS – UEFISCDI (project number PN-III-P1-1.1-TE-2021-0165, within PNCDI III), implemented through the Babeș Bolyai University (Cluj-Napoca), PI Dr. Rada Varga.

The research for this publication has been supported by a grant from the Priority Research Area Heritage under the Strategic Programme Excellence Initiative at Jagiellonian University.

Wolfgang Spickermann

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 13-28

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.001.19151Annamária Izabella Pázsint

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 29-38

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.002.19152Ivo Topalilov

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 39-49

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.003.19153Lucrețiu Mihailescu-Bîrliba, Petre Colțeanu

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 51-62

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.004.19154Roxana-Gabriela Curcă

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 63-69

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.005.19155Zdravko Dimitrov

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 71-82

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.006.19156Cristina Crizbășan

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 83-100

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.007.19157Ana Honcu

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 101-106

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.008.19158Sorin Nemeti

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 107-125

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.009.19159Rada Varga, Alexander Rubel, George Bounegru

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 127-141

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.010.19160Péter Kovács

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 143-151

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.011.19161Chiara Cenati, Peter Kruschwitz

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 153-183

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.012.19162Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 185-188

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.013.19163Tomasz Grabowski

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 189-191

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.014.19164Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 193-196

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.015.19165Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 197-200

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.016.19166Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 201-203

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.017.19167Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 205-207

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.018.19168Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 209-211

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.019.19169Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 213-215

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.020.19170Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 185-188

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.013.19163Tomasz Grabowski

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 189-191

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.014.19164Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 193-196

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.015.19165Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 197-200

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.016.19166Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 201-203

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.017.19167Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 205-207

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.018.19168Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 209-211

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.019.19169Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 213-215

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.020.19170Wolfgang Spickermann

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 13-28

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.001.19151Annamária Izabella Pázsint

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 29-38

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.002.19152Ivo Topalilov

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 39-49

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.003.19153Lucrețiu Mihailescu-Bîrliba, Petre Colțeanu

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 51-62

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.004.19154Roxana-Gabriela Curcă

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 63-69

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.005.19155Zdravko Dimitrov

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 71-82

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.006.19156Cristina Crizbășan

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 83-100

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.007.19157Ana Honcu

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 101-106

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.008.19158Sorin Nemeti

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 107-125

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.009.19159Rada Varga, Alexander Rubel, George Bounegru

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 127-141

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.010.19160Péter Kovács

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 143-151

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.011.19161Chiara Cenati, Peter Kruschwitz

ELECTRUM, Volume 31, 2024, pp. 153-183

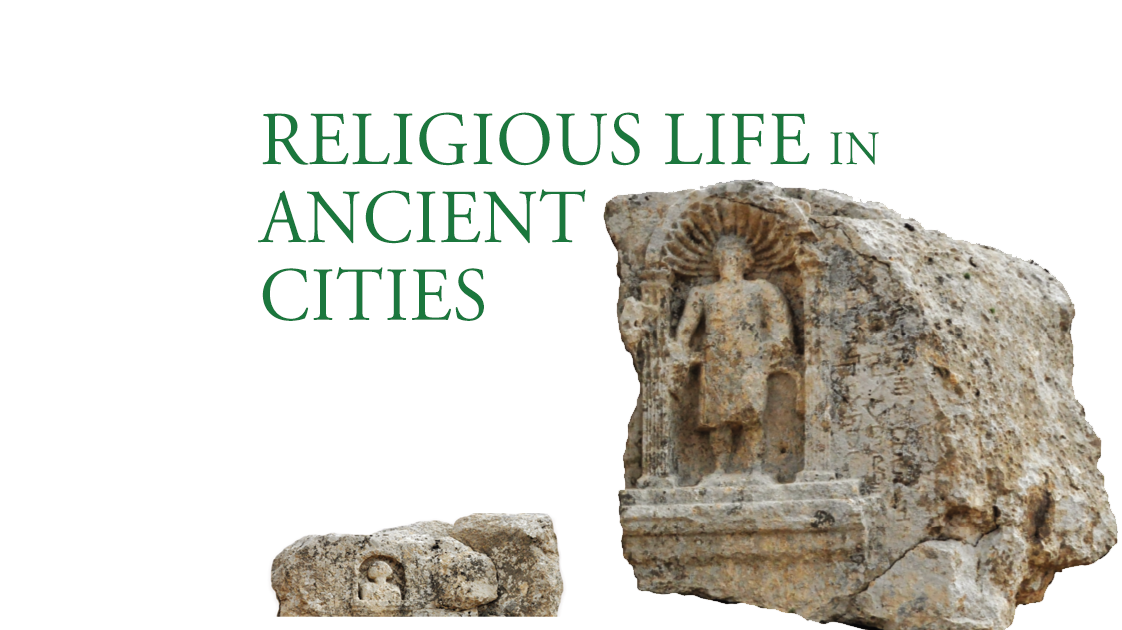

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.24.012.19162Publication date: 26.06.2023

Editor-in-Chief: Edward Dąbrowa

Cover Design: Barbara Widłak

Cover photography: Sumatar, sacred mount, rock reliefs

The research for this publication has been supported by a grant from the Priority Research Area Heritage under the Strategic Programme Excellence Initiative at Jagiellonian University.

Edward Dąbrowa, Sławomir Sprawski

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 7-9

Micaela Canopoli

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 13-36

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.001.17318Nanaia is a Babylonian deity who was associated with Artemis in Hellenistic times. She is identified as a moon goddess as well as a deity of love and war, and as a protector of the sovereign and the country. The reason behind the assimilation between this oriental deity and Artemis lay in the commonality of functions between the two. The presence of a goddess called Artemis Nanaia is attested in Attica by an inscription found at Piraeus which is the only testimony of the presence of this cult in Greece. Like the goddess Nanaia, Artemis was a moon goddess, identified as a protector of political order. This function in Attica is expressed by the adjective Boulaia and by the practice, widespread since the second century B.C., of offering a sacrifice to Artemis Boulaia and Artemis Phosphoros before political assemblies in the Athenian Agora.

The aim of this paper is to put into perspective the characteristics of the cults of Artemis Nanaia as attested in two important sanctuaries in the Middle East, including the sanctuary of Nanaia at Susa and the sanctuary of Artemis Nanaia at Dura-Europos, with the testimonies related to the cult of Artemis attested at Piraeus. The testimonies, and the characteristics of the cult attested in these three areas will be analysed together in order to etter understand the reasons behind the dedication of Axios and Kapo and its original location.

Ivo Topalilov

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 37-53

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.002.17319The article deals with the early history of the politeia Messambria Pontica through the prysm of the foundation myth and cult. The almost simultaneous establishment of the cult and myth to the historical founder and mythical eponumous hero-founder attested on the silver coinage of Messambria may refer to a certain need of a group of Messambrian society to present itself in a certain way at-home and abroad. The author elieves that this should be considered within the ethnic discourse between Ionians and Dorians.

Elena Santagati

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 55-74

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.003.17320This paper aims to investigate the reasons why, since the reign of Philip II, the “national” Zeus, venerated on Olympus and Dion and characterized by the oak crown, was abandoned in favor of the Olympian Zeus of Elis, characterized by the olive/oleaster wreath. We notice that while the members of the royal family display, in life and death, an oak wreath as an insignia of their kingship, and at the same time also as a symbol of their highest divinity, the kings themselves issue the image of the panhellenic god with an olive/laurel wreath on their coins.

Stefano G. Caneva

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 75-101

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.004.17321The history of Hellenistic Pergamon is deeply affected by the dual status of a polis that also functioned as a dynastic residence. This overlap between civic and royal institutions significantly impacted the political life of the city. This paper contributes to the ongoing debate about honorific habits and the consolidation of the civic elite of Pergamon by focusing on the triangular interactions between the Attalids, their court, and the polis’ institutions in the period from Eumenes I to Attalos III. To do so, several dossiers concerning the priesthoods and religious liturgies of Attalid Pergamon will be reassessed by paying attention to their tenure, appointment, privileges, and the social groups that held these charges.

Catharine C. Lorber

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 103-195

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.005.17322The paper provides a dossier of honors offered to Seleukid and Ptolemaic kings, preceded by a brief introduction.

Hadrien Bru

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 197-209

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.006.17323In order to study the cult of Zeus Nikatôr, six Greek inscriptions (one from northern Syria and five from southern Anatolia) are gathered and commented. The origin, the diffusion and the longevity of the cult are evoked, since it was vivid until the IIIrd century A.D. in the eastern Mediterranean, mainly in southern Taurus (Pamphylia, Lycia, Pisidia and Phrygia Paroreios). Accordingly, also in connection with onomastics and numismatics, the Seleucid memory and the remembrance of Seleucos I are discussed, from Hellenistic times to the Roman Imperial period, and beyond.

Anna Heller

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 211-233

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.007.17324In ancient Greek cities, the organization of festivals generated its own institutional system, with various officials involved in various aspects of the celebration. One of these officials was the panegyriarch, in charge of the market that took place during the festival. On the basis of a systematic survey of the epigraphic documentation, this paper aims at defining the profile of the individuals attested as panegyriarchs. It presents the chronological and geographical distribution of the evidence, studies the offices associated with that of panegyriarch within civic careers and reflects on the level of prestige of this specific magistracy.

Axel Filges

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 235-272

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.008.17325The interpretation of figures of deities on the reverse of the coins of Asia Minor cities of the imperial period is usually done in several steps. The deity is generally quickly determined. It is difficult, however, to establish the superior intention behind the depiction. Does the figure refer to a real cult statue of the emitting city, is the image ‘only’ a reference to a local cult or was it chosen to symbolise, for instance, political connections of cities?

The essay brings together opinions from 140 years of international numismatic scholarship and thus offers an overview of the changing patterns of interpretation as well as their range in general. In the end, a more conscious approach to the figures of the gods on coins and a more reflective methodological approach are recommended.

Anna Tatarkiewicz

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 273-292

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.009.17326The article addresses the issue of Mithraism in Ostia. It discusses the latest discoveries, the nature of the Mithra cult in Ostia, with particular emphasis on the place of Mithra’s shrines in the city space.

Aleksandra Kubiak-Schneider

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 293-306

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.010.17327The epigraphic record from Palmyra brings light on the organization of the temples: personnel, management of feasts, economy and on the ritual practices towards certain deities like Allat and Shai ‘al-Qaum. These texts were previously called in the research literature “sacred laws”and what the scholarly debate nowadays labels with the term “ritual norms.”The aim of this paper, divided on the temple economy and personnel, and ritual behavior, is to understand through the scraps of information the administration of the Palmyrene temples and processes which shaped the life in the places of worship.

Michael Blömer

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 307-338

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.011.17328Today the city of Ḫarrān/Carrhae is mainly known for the famous battle, in which the Roman general Crassus was defeated by a Parthian army in 53 BCE. However, Ḫarrān was also one of the most important religious centres of North Mesopotamia. Since the Bronze Age, the moon god Sîn of Ḫarrān was popular in the wider region, and it is well known that the late Assyrian and Babylonian kings supported the cult and rebuilt the temple of Sîn. Archaeological evidence and written sources attest to the great popularity of Sîn of Ḫarrān at that time. Much less is known about the development of the cult in the subsequent periods, but the evidence assembled in this paper indicates that it continued to thrive. An important but so far largely ignored source for the study of Sîn are coins, which were minted at Ḫarrān in the second and third century CE. They suggest that some distinctive features of the Iron Age cult still existed in the Roman period. Most important in this regard is the predominance of aniconic symbolism. A cult standard, a crescent on a globe with tassels mounted on a pole, continued to be the main of representation of the god. In addition, two versions of an anthropomorphic image of the god can be traced in the coinage of Ḫarrān. The first shows him as an enthroned mature man. It is based on the model of Zeus, but his attributes identify the god as Sîn. The second version portrays him as a youthful, beardless god.

Late antique sources frequently mention that the people of Ḫarrān remained attached to pagan religion, but the veracity of these accounts must be questioned. A reassessment of the literary and archaeological evidence suggests that the accounts of a pagan survival at Ḫarrān are hyperbolic and exacer ated by negative sentiments towards Ḫarrān among writer from the neighbouring city of Edessa.

Carmen Alarcón Hernández, Fernando Lozano Gómez

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 339-352

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.012.17329There are abundant examples of negative assessments of cultic honors to Roman emperors by nineteenth- and twentieth-century researchers. In the minds of historians raised in modern societies, in which monotheistic Abrahamic religions usually reign supreme, this is a completely understandable a priori approach; nevertheless, it hinders a correct understanding of Roman society in antiquity. This paper examines the need to provide a complex answer to the question of whether the inhabitants of the Roman world really believed in the divinity of their rulers. A complex answer to the question can only emerge from a historical contextualization of the phenomenon under analysis, an examination of the imperial cult within the wider changes that were taking place in Roman religion at the time, and application of the necessary empathetic approach.

Martha W. Baldwin Bowsky

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 353-399

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.013.17330Forty years after the publication of Sanders’ Roman Crete, a broader range of evidence for the imperial cult on Crete is available—temples and other structures, monumental architectural members, imperial altars, portraiture and statuary, coinage, statue and portrait bases, other inscriptions, priest and high priests, members and archons of the Panhellenion, and festivals—and far more places can now be identified as cities participating in the imperial cult. This evidence can be set into multiple Cretan contexts, beginning with the establishment and evolution of the imperial cult across Crete, before locating the imperial cult in the landscape of Roman Crete. The ultimate Cretan contexts are the role of emperor worship in the lives of the island’s population, as it was incorporated into Cretan religious and social systems.

Marco Vitale

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 401-440

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.014.17331The provincial imperial cult represents one of the most relevant expressions of multiform relationship between provincial communities and Roman authorities especially in the East. During the Roman Principate in Syria, we can enumerate seven administrative districts (eparchies) which occur in connection with this political and religious phenomenon. The complicated question of how the province-wide worship of the Imperial family was organised in Roman Levant must be analysed in different terms. Important aspects are the Roman territorial framework of administration, the creation of autonomous city-leagues (koiná) and their cultic functions, the rules of membership within these federal organizations and their self-representation in coinages and inscriptions. On the level of political and financial management, we are dealing with federal officials and the festivities organized by them. Our paper aims to give a detailed overview of the Syrian imperial cult related not only to one specific site, but in the context of a large and culturally complex area.

Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 441-443

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.015.17332Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 445-447

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.016.17333Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 449-451

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.017.17334Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 453-455

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.018.17335Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 457-459

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.019.17336Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 461-463

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.020.17337Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 465-466

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.021.17338Chandler A. Collins

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 467-469

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.022.17339Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 441-443

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.015.17332Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 445-447

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.016.17333Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 449-451

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.017.17334Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 453-455

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.018.17335Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 457-459

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.019.17336Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 461-463

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.020.17337Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 465-466

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.021.17338Chandler A. Collins

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 467-469

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.022.17339Edward Dąbrowa, Sławomir Sprawski

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 7-9

Micaela Canopoli

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 13-36

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.001.17318Nanaia is a Babylonian deity who was associated with Artemis in Hellenistic times. She is identified as a moon goddess as well as a deity of love and war, and as a protector of the sovereign and the country. The reason behind the assimilation between this oriental deity and Artemis lay in the commonality of functions between the two. The presence of a goddess called Artemis Nanaia is attested in Attica by an inscription found at Piraeus which is the only testimony of the presence of this cult in Greece. Like the goddess Nanaia, Artemis was a moon goddess, identified as a protector of political order. This function in Attica is expressed by the adjective Boulaia and by the practice, widespread since the second century B.C., of offering a sacrifice to Artemis Boulaia and Artemis Phosphoros before political assemblies in the Athenian Agora.

The aim of this paper is to put into perspective the characteristics of the cults of Artemis Nanaia as attested in two important sanctuaries in the Middle East, including the sanctuary of Nanaia at Susa and the sanctuary of Artemis Nanaia at Dura-Europos, with the testimonies related to the cult of Artemis attested at Piraeus. The testimonies, and the characteristics of the cult attested in these three areas will be analysed together in order to etter understand the reasons behind the dedication of Axios and Kapo and its original location.

Ivo Topalilov

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 37-53

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.002.17319The article deals with the early history of the politeia Messambria Pontica through the prysm of the foundation myth and cult. The almost simultaneous establishment of the cult and myth to the historical founder and mythical eponumous hero-founder attested on the silver coinage of Messambria may refer to a certain need of a group of Messambrian society to present itself in a certain way at-home and abroad. The author elieves that this should be considered within the ethnic discourse between Ionians and Dorians.

Elena Santagati

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 55-74

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.003.17320This paper aims to investigate the reasons why, since the reign of Philip II, the “national” Zeus, venerated on Olympus and Dion and characterized by the oak crown, was abandoned in favor of the Olympian Zeus of Elis, characterized by the olive/oleaster wreath. We notice that while the members of the royal family display, in life and death, an oak wreath as an insignia of their kingship, and at the same time also as a symbol of their highest divinity, the kings themselves issue the image of the panhellenic god with an olive/laurel wreath on their coins.

Stefano G. Caneva

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 75-101

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.004.17321The history of Hellenistic Pergamon is deeply affected by the dual status of a polis that also functioned as a dynastic residence. This overlap between civic and royal institutions significantly impacted the political life of the city. This paper contributes to the ongoing debate about honorific habits and the consolidation of the civic elite of Pergamon by focusing on the triangular interactions between the Attalids, their court, and the polis’ institutions in the period from Eumenes I to Attalos III. To do so, several dossiers concerning the priesthoods and religious liturgies of Attalid Pergamon will be reassessed by paying attention to their tenure, appointment, privileges, and the social groups that held these charges.

Catharine C. Lorber

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 103-195

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.005.17322The paper provides a dossier of honors offered to Seleukid and Ptolemaic kings, preceded by a brief introduction.

Hadrien Bru

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 197-209

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.006.17323In order to study the cult of Zeus Nikatôr, six Greek inscriptions (one from northern Syria and five from southern Anatolia) are gathered and commented. The origin, the diffusion and the longevity of the cult are evoked, since it was vivid until the IIIrd century A.D. in the eastern Mediterranean, mainly in southern Taurus (Pamphylia, Lycia, Pisidia and Phrygia Paroreios). Accordingly, also in connection with onomastics and numismatics, the Seleucid memory and the remembrance of Seleucos I are discussed, from Hellenistic times to the Roman Imperial period, and beyond.

Anna Heller

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 211-233

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.007.17324In ancient Greek cities, the organization of festivals generated its own institutional system, with various officials involved in various aspects of the celebration. One of these officials was the panegyriarch, in charge of the market that took place during the festival. On the basis of a systematic survey of the epigraphic documentation, this paper aims at defining the profile of the individuals attested as panegyriarchs. It presents the chronological and geographical distribution of the evidence, studies the offices associated with that of panegyriarch within civic careers and reflects on the level of prestige of this specific magistracy.

Axel Filges

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 235-272

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.008.17325The interpretation of figures of deities on the reverse of the coins of Asia Minor cities of the imperial period is usually done in several steps. The deity is generally quickly determined. It is difficult, however, to establish the superior intention behind the depiction. Does the figure refer to a real cult statue of the emitting city, is the image ‘only’ a reference to a local cult or was it chosen to symbolise, for instance, political connections of cities?

The essay brings together opinions from 140 years of international numismatic scholarship and thus offers an overview of the changing patterns of interpretation as well as their range in general. In the end, a more conscious approach to the figures of the gods on coins and a more reflective methodological approach are recommended.

Anna Tatarkiewicz

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 273-292

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.009.17326The article addresses the issue of Mithraism in Ostia. It discusses the latest discoveries, the nature of the Mithra cult in Ostia, with particular emphasis on the place of Mithra’s shrines in the city space.

Aleksandra Kubiak-Schneider

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 293-306

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.010.17327The epigraphic record from Palmyra brings light on the organization of the temples: personnel, management of feasts, economy and on the ritual practices towards certain deities like Allat and Shai ‘al-Qaum. These texts were previously called in the research literature “sacred laws”and what the scholarly debate nowadays labels with the term “ritual norms.”The aim of this paper, divided on the temple economy and personnel, and ritual behavior, is to understand through the scraps of information the administration of the Palmyrene temples and processes which shaped the life in the places of worship.

Michael Blömer

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 307-338

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.011.17328Today the city of Ḫarrān/Carrhae is mainly known for the famous battle, in which the Roman general Crassus was defeated by a Parthian army in 53 BCE. However, Ḫarrān was also one of the most important religious centres of North Mesopotamia. Since the Bronze Age, the moon god Sîn of Ḫarrān was popular in the wider region, and it is well known that the late Assyrian and Babylonian kings supported the cult and rebuilt the temple of Sîn. Archaeological evidence and written sources attest to the great popularity of Sîn of Ḫarrān at that time. Much less is known about the development of the cult in the subsequent periods, but the evidence assembled in this paper indicates that it continued to thrive. An important but so far largely ignored source for the study of Sîn are coins, which were minted at Ḫarrān in the second and third century CE. They suggest that some distinctive features of the Iron Age cult still existed in the Roman period. Most important in this regard is the predominance of aniconic symbolism. A cult standard, a crescent on a globe with tassels mounted on a pole, continued to be the main of representation of the god. In addition, two versions of an anthropomorphic image of the god can be traced in the coinage of Ḫarrān. The first shows him as an enthroned mature man. It is based on the model of Zeus, but his attributes identify the god as Sîn. The second version portrays him as a youthful, beardless god.

Late antique sources frequently mention that the people of Ḫarrān remained attached to pagan religion, but the veracity of these accounts must be questioned. A reassessment of the literary and archaeological evidence suggests that the accounts of a pagan survival at Ḫarrān are hyperbolic and exacer ated by negative sentiments towards Ḫarrān among writer from the neighbouring city of Edessa.

Carmen Alarcón Hernández, Fernando Lozano Gómez

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 339-352

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.012.17329There are abundant examples of negative assessments of cultic honors to Roman emperors by nineteenth- and twentieth-century researchers. In the minds of historians raised in modern societies, in which monotheistic Abrahamic religions usually reign supreme, this is a completely understandable a priori approach; nevertheless, it hinders a correct understanding of Roman society in antiquity. This paper examines the need to provide a complex answer to the question of whether the inhabitants of the Roman world really believed in the divinity of their rulers. A complex answer to the question can only emerge from a historical contextualization of the phenomenon under analysis, an examination of the imperial cult within the wider changes that were taking place in Roman religion at the time, and application of the necessary empathetic approach.

Martha W. Baldwin Bowsky

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 353-399

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.013.17330Forty years after the publication of Sanders’ Roman Crete, a broader range of evidence for the imperial cult on Crete is available—temples and other structures, monumental architectural members, imperial altars, portraiture and statuary, coinage, statue and portrait bases, other inscriptions, priest and high priests, members and archons of the Panhellenion, and festivals—and far more places can now be identified as cities participating in the imperial cult. This evidence can be set into multiple Cretan contexts, beginning with the establishment and evolution of the imperial cult across Crete, before locating the imperial cult in the landscape of Roman Crete. The ultimate Cretan contexts are the role of emperor worship in the lives of the island’s population, as it was incorporated into Cretan religious and social systems.

Marco Vitale

ELECTRUM, Volume 30, 2023, pp. 401-440

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.23.014.17331The provincial imperial cult represents one of the most relevant expressions of multiform relationship between provincial communities and Roman authorities especially in the East. During the Roman Principate in Syria, we can enumerate seven administrative districts (eparchies) which occur in connection with this political and religious phenomenon. The complicated question of how the province-wide worship of the Imperial family was organised in Roman Levant must be analysed in different terms. Important aspects are the Roman territorial framework of administration, the creation of autonomous city-leagues (koiná) and their cultic functions, the rules of membership within these federal organizations and their self-representation in coinages and inscriptions. On the level of political and financial management, we are dealing with federal officials and the festivities organized by them. Our paper aims to give a detailed overview of the Syrian imperial cult related not only to one specific site, but in the context of a large and culturally complex area.

Publication date: 21.10.2022

Editor-in-Chief: Edward Dąbrowa

Dofinansowanie czasopism w modelu otwartego dostępu OA (edycja I) POB Heritage – Program Strategiczny Inicjatywa Doskonałości w Uniwersytecie Jagiellońskim

Cover design: Barbara Widłak

Cover photography: Aphrodite Anadyomene, Nisa

Sławomir Sprawski

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 11-12

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.001.15771Paola Piacentini

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 13-21

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.002.15772Thomas Harrison

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 23-37

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.003.15773This paper reviews the different models commonly used in understanding Herodotus’evidence on the Achaemenid Persian empire. It suggests that these approaches—for example, the assessment of Herodotus’accuracy, of the level of his knowledge, or of his sympathy for the Persians—systematically underestimate the complexity of his (and of the Greeks’) perspective on the Persian empire: the conflicted perspective of a participant rather than just a detached observer.

Sabine Müller

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 39-51

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.004.15774There is a lot of uncertainty about the attribution of fragments to either Marsyas of Pella or Marsyas of Philippi. This paper challenges the traditional attribution of BNJ 135–136 F 4 (mentioning Midas’chariot with the Gordian knot) to Marsyas of Philippi and argues in favor of the identification of Marsyas of Pella as the author. For ideological and propagandistic reasons, it would fit well into Marysas of Pella’s account of the roots of Argead rule in his first book. By referring to Midas, Marsyas would have been able to link his half-brother Antigonus as the contemporary governor of Phrygia not only with the legendary Phrygian king and his legacy, but also with a Macedonian logos attested by Herodotus, creating a connection between Midas and the foundation of Argead rule. According to this logos, there existed old kinship relations between Macedonians and Phrygians who used to dwell at the foot of Mt. Bermium and were called Briges. This tradition was of propagandistic value and could have served to increase the ideological value of Antigonus’satrapy and main base in the rivalry with the other Diadochs.

Catharine C. Lorber

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 53-72

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.005.15775Cultic and other honors offered to rulers by their subjects unambiguously express loyalty to the rulers. Based on data collected for the Seleukid and Ptolemaic empires, a comparison is offered emphasizing the particular qualities of the Seleukid record. The comparison considers geographic distribution, where the honors fell on a public to private spectrum, the occupations and ethnicities of the subjects who offered honors individually, the intensity of these practices, and changes in the patterns over time. We know in advance that honors for the rulers are weakly attested for the Seleukid east, and even in Koile Syria and Phoinike. Should this reticence be interpreted as a possible indication of tepid support for Seleukid rule in these regions? Alternative explanations or contributing factors include preexisting cultural habits, different royal policies, destruction of evidence by wars and natural disasters, and the unevenness of archaeological exploration.

Antonio Invernizzi

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 73-86

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.006.15776The name of Rodogune was not applied only to the well known statuette of Aphrodite Anadyomene from Parthian Nisa, but also to a seal impressed on a sealing from the Nisa Square House. Although the attribution of the seal, unlike that of the statuette, was not discussed in detail, the portrait depicted on it was recognized as that of the Arsacid princess. Actually, the head is not female, but male, and can in all likelihood be that of Apollo with a laurel wreath. The style of execution suggests a relatively late date for the seal, not before the end of the 1st century BC –1st century AD, and allows its impression to be included in the general group of sealings from the Square House of Nisa.

Fabrizio Sinisi

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 87-107

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.007.15777The question of the identity of the issuer of the so-called “Heraios”coinage is analysed, and it is proposed that these series be ascribed to Kujula Kadphises, as already suggested by some scholars. In this regard, the circulation of these coins and the connections established by their imagery are focused upon. Some possible inferences on the original location of Kujula Kadphises are discussed in the concluding part, hypothesizing a southern context different from the northern one commonly ascribed to the founder of the Kushan dynasty.

Achim Lichtenberger, Cornelius Meyer, Torben Schreiber, Mkrtich H. Zardaryan

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 109-125

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.008.15778In March of 2021, the Berlin-based company cmp continued geophysical prospection works at the ancient city of Artashat-Artaxata (Ararat Province, Armenia). The city was founded by Artashes-Artaxias I in the early 2nd century BC and served as his capital. First magnetic measurements were conducted by the Eastern Atlas company in September 2018. In 2021, during the 5-day survey a total surface of approximately 19.5 ha was investigated by use of the LEA MAX magnetic gradiometer array. This system was configured with seven fluxgate gradiometer probes, similar to the system used in the first survey of 2018. The investigated areas of the Eastern Lower City of Artaxata, located to the south of the investigated field of 2018, had good surface conditions with a moderate amount of sources causing disturbance. However, the general level of the magnetic gradient values measured was significantly lower compared to the 2018 data. Despite the lower magnetic field intensity, a continuation of linear structures towards the south was observed. These lines, most likely reflecting streets and pathways, criss-cross the central part of the Eastern Lower City in a NW–SE and NE–SW direction and exhibit partly positive, partly negative magnetic anomalies. Attached to them, some isolated spots with building remains were identified. The negative linear anomalies point to remains of limestone foundations, as detected in the northern part of the Lower City. The low magnetic intensity and fragmentation of the observed structures are most likely due to severe destruction of the ancient layers by 20th-century earthworks for agricultural purposes. Moreover, the southern part of the surveyed area was affected by major changes caused by modern quarries at Hills XI and XII. In general, the results of the two magnetic prospection campaigns greatly aid our understanding of the archaeological situation in the area of the Eastern Lower City of Artaxata, justifying further investigations that will surely contribute to greater contextualization of the identified archaeological structures. The full data sets are also published in open access on Zenodo.

Judean Piracy, Judea and Parthia, and the Roman Annexation of Judea: The Evidence of Pompeius Trogus

Kenneth Atkinson

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 127-145

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.009.15779Pompey the Great’s 63 BCE conquest of the Jewish kingdom known as the Hasmonean State has traditionally been viewed as an inevitable event since the Roman Republic had long desired to annex the Middle Eastern nations. The prevailing consensus is that the Romans captured the Hasmonean state, removed its high-priest kings from power, and made its territory part of the Republic merely through military force. However, Justin’s Epitome of the Philippic Histories of Pompeius Trogus is a neglected source of new information for understanding relations between the Romans and the Jews at this time. Trogus’s brief account of this period alludes to a more specific reason, or at least, circumstance for Pompey’s conquest of Judea. His work contains evidence that the Jews were involved in piracy, of the type the Republic had commissioned Pompey to eradicate. In addition to this activity that adversely affected Roman commercial interests in the Mediterranean, the Jews were also involved with the Seleucid Empire and the Nabatean Arabs, both of whom had dealings with the Parthians. Piracy, coupled with Rome’s antagonism towards the Parthians, negatively impacted the Republic’s attitude towards the Jews. Considering the evidence from Trogus, Roman fears of Jewish piracy and Jewish links to the Republic’s Parthian enemies were not unfounded.

Lucia Visonà

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 147-160

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.010.15780In the Parallel Lives, Aristides and Themistocles are two antithetical characters. This opposition, already present in Herodotus’work and common to the literary tradition of the Persian wars, is particularly emphasized by Plutarch who shapes two characters endowed with opposing character traits who adopt completely different behaviors towards friends or wealth. This profound contrast is intended to highlight the collaboration between the two Athenians, ready to put aside personal differences to devote themselves together to the war against the Persians. The episode of reconciliation is in fact located, unlike other sources (Aristotle, Diodorus), before the battle of Salamis. However, Aristides and Themistocles do not limit themselves to settling their differences : they also take on the role of mediators during the war in order to address the disagreements between Athens and the other Greek cities and avoid hindering the common struggle against the barbarians. To do this, Plutarch adapts some passages of Herodotus (directly or by choosing sources that made such changes) to insert the protagonists of the Lives and create a climate of tension that they can happily resolve. His authorial choices appear consistent with the criticisms against Herodotus in De Herodoti Malignitate. The reflection about the Persian wars in Plutarch’s corpus seems therefore to be animated by a coherent vision, born from the tradition elaborated by the Attic orators in the fourth century : the conflict is seen as a privileged moment of the union between the Greeks, capable of overcoming the almost endemic rivalries that oppose them in view of the common good.

Werner Eck

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 161-169

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.011.15781Several recently discovered lead ingots refer to mining districts in the region of present-day Kosovo. Of particular interest is an ingot with the inscription metallo(rum) Messalini, which refers to M. Valerius Messala Messalinus Corvinus (cos. ord. 3 BC), who was employed as a commander during the Pannonian-Dalmatian uprising of 6–9 AD. He was obviously one of the senators whom Augustus not only honoured with awards for their service, but whom he also supported economically, not unlike Cn. Calpurnius Piso (cos. ord. 7 BC), who had received saltus in Illyricum. These gifts served to create loyalty; but they were precarious gifts because when loyalty ceased, they were reclaimed for the imperial patrimonium.

David M. Jacobson

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 171-196

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.012.15782Without having any contemporaneous account of the Bar Kokhba Revolt comparable to the writings of Josephus that describe the First Jewish Revolt, our knowledge about many aspects of the later uprising is rather sketchy. The publication of Roman military diplomas and the remarkable series of documents recovered from caves in the Judaean Desert, along with other major archaeological findings, has filled in just some of missing details. This study is devoted to a reexamination of the rebel coinage. It has highlighted the importance of the numismatic evidence in helping to elucidate the religious ideology that succoured the rebellion and shaped its leadership.

Oliver Stoll

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 197-217

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.013.15783This article examines defeats and losses as phenomena of an ‘expanded military history’ of Roman History from the Republic to the Principate. It adopts a cultural historical perspective of the military historical phenomenon. “Patterns”and “strategies”are defined, that appear in the sources when dealing with Roman defeats, losses and losers (in particular the commanders or even the emperor himself). Above, the historiography of the Roman imperial period is exemplary examined to see what reasons, interpretations or explanations are given there for suffering a defeat and whether and how these are part of narrative strategies. Sometimes military catastrophes simply were concealed, belittled or reinterpreted. How Rome dealt with defeat tells something about Rome’s society and especially the elite: “Roman culture”or “Rome’s political culture” shaped the way how the military phenomenon of defeat was dealt with. Defeats could also be seen as chances for future victories, they were good for learning and examples for withstanding with the help of morale and disciplina. In the end Rome’s strategies in dealing with such catastrophic events of ‘military history’overall seem to paint the picture of Rome as a resilient socio-political and military system!

Aleksandra Kubiak-Schneider, Achim Lichtenberger

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 219-236

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.014.15784The finds from the ancient city of Gerasa brought in 1930’two inscriptions dated to the second half of the 1st century CE which mention the deity called Pakeidas. The aim of this paper is to discuss Pakeidas and his relation to another god labelled Theos Arabikos worshipped in the same city. The authors make a broad Semitic overview on the etymology of the name Pakeidas looking at the West and East (Akkadian) Semitic evidence. The authors discuss the possible location of the temple dedicated to this god beneath the Cathedral. They also reexamine in the light of epigraphic sources in comparison to the Aramaic material from the Near East the function of archibomistai, cultic agents who served to this local god.

Peter Franz Mittag

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 237-247

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.015.15785Especially in regard to the multitude of depictions on coins and medallions referring to the history of Rome in the early 140s, the omission of corresponding depictions in the year 147/148, when Rome’s birthday was celebrated for the 900th time, is remarkable. Instead of referring to this important event, the coins and medallions of Antoninus Pius present themselves entirely under the sign of his decennalia. Apparently, the reference to the anniversary of the reign was considered more important than Rome’s birthday. Reasons for this decision could have been problems of acceptance, which are only hinted at in the literary sources, which are consistently friendly to Antoninus.

Giusto Traina

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 249-259

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.016.15786Some evidence points at the presence of Orientals in late Roman Italy: traders (labelled “Syrians”), petty sellers (the pantapolae in Nov. Val. 5), but also students, professors such as Ammianus Marcellinus, or pilgrims. Although being Roman citizens, nonetheless they were considered foreign individuals, subject to special restrictions. The actual strangers made a different case, especially the Persians. The situation of foreign individuals was quite different. Chauvinistic attitudes are widely attested, and they worsened in critical periods, for example after Adrianople. This may explain the laws of early 397 and June 399, promulgated during Stilicho’s regency, which prohibited the wearing of trousers (bracae) and some fashionable boots called tzangae. Of course, some protégés of the imperial court had the right to enter Italy, as it was the case of the Sassanian prince Hormisdas, who accompanied Constantius II in his visit of Rome in 357.

Simone Rendina

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 261-266

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.017.15787In Themistius’orations there are many clear and direct references to the Greek literature of the 5th and 4th centuries BCE. However, there are also more subtle references to these classical texts. In this paper, two references to classical Greek historiography are identified in Themistius’Oration 18. As we shall see, in order to praise the refashioning of Constantinople by Theodosius the Great, Themistius subtly quoted a passage by Xenophon. In order to highlight the splendour of the city of Constantinople, he also used as a reference one of the most eminent classical encomia of cities, that is, Pericles’funeral oration from the second book of Thucydides’ History. Both references served to enhance Themistius’already good relations with Theodosius I, who had recently renovated Constantinople with new monuments. This research thus stresses the relevance of quotations in Themistius’orations when studying his political agenda, including quotations that are less obvious and less easily identifiable.

Touraj Daryaee

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 267-284

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.018.15788This essay discusses the importance of Ctesiphon in the historical and literary tradition of Sasanian and Post-Sasanian Iran. It is proposed that there was a significant buildup of the Ctesiphon’s defenses in the third century that it made its conquest by the Roman Empire impossible and its gave it an aura of impregnability. By the last Sasanian period the city was not only inhabited by Iranian speaking people and a capital, but it also became part of Iranian lore and tradition, tied to mythical Iranian culture-heroes and kings. Even with the fall of the Sasanian Empire, in Arabic and Persian poetry the grandeur and memory of Ctesiphon was preserved as part of memory of the great empires of the past.

Michael Whitby

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 285-300

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.019.15789The homily on the Avar siege of Constantinople in 626 attributed to Theodore Syncellus shares numerous linguistic features both with Theodore’s homily of 623 on the Virgin’s Robe and with George of Pisidia’s poem of 626/7 on the siege. Theodore and George both celebrate the combined efforts of Patriarch Sergius and the Virgin Mary in saving the city, but Theodore also highlights the involvement of other agents, in particular the patrician Bonus and the young Heraclius Constantine, who were jointly in charge of the city while Emperor Heraclius was campaigning against the Persians. The homily is structured around the exegesis of three Old Testament passages: the promise in Isaiah 7 to King Ahaz about the salvation of Jerusalem; the analysis of numbers in Zachariah 8.19; and God’s destruction of Gog and Magog in Ezekiel 38–39.

Simon James

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 301-328

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.029.16524The centenary of the establishment of the Department of Classics at the University of Kraków coincides with that of the beginnings of the study of the ‘Pompeii of the Syrian Desert.’In spring 1920, British Indian soldiers digging in the ruins known as Salihiyeh overlooking the Euphrates accidentally revealed ancient paintings. Recorded by archaeologist James Henry Breasted, these discoveries would soon lead to further excavations by Franz Cumont (1922–1923), and eventually to the great Yale-French Academy expedition under Mikhail Rostovtzeff (1928–1937). By then the site was famous as ‘Dura-Europos,’giving us remarkable insights into Hellenistic Greek, Parthian, Roman, early Christian and Jewish life in the Middle East. Not the least of the discoveries related to the soldiers of Dura’s Roman garrison. This paper traces the history of the revelation—and, in part, invention—of Dura-Europos in the 1920s. It is a story of eminent scholars, but also of others who actually revealed the evidence: soldiers, both officers and men, of the armies of the British and French empires which dominated the region at the time. Today, at a time of ‘decolonisation’of scholarship, the very formulation ‘Dura-Europos’itself is a subject of contention.

Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 329-332

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.020.15790Tomasz Zieliński

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 333-336

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.021.15791Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 337-339

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.022.15792Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 341-343

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.023.15793Maciej Piegdoń

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 345-346

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.024.15794Maciej Piegdoń

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 347-349

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.025.15795Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 351-353

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.026.15796Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 355-357

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.027.15797Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 359-361

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.028.15798Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 329-332

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.020.15790Tomasz Zieliński

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 333-336

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.021.15791Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 337-339

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.022.15792Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 341-343

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.023.15793Maciej Piegdoń

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 345-346

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.024.15794Maciej Piegdoń

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 347-349

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.025.15795Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 351-353

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.026.15796Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 355-357

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.027.15797Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 359-361

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.028.15798Sławomir Sprawski

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 11-12

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.001.15771Paola Piacentini

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 13-21

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.002.15772Thomas Harrison

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 23-37

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.003.15773This paper reviews the different models commonly used in understanding Herodotus’evidence on the Achaemenid Persian empire. It suggests that these approaches—for example, the assessment of Herodotus’accuracy, of the level of his knowledge, or of his sympathy for the Persians—systematically underestimate the complexity of his (and of the Greeks’) perspective on the Persian empire: the conflicted perspective of a participant rather than just a detached observer.

Sabine Müller

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 39-51

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.004.15774There is a lot of uncertainty about the attribution of fragments to either Marsyas of Pella or Marsyas of Philippi. This paper challenges the traditional attribution of BNJ 135–136 F 4 (mentioning Midas’chariot with the Gordian knot) to Marsyas of Philippi and argues in favor of the identification of Marsyas of Pella as the author. For ideological and propagandistic reasons, it would fit well into Marysas of Pella’s account of the roots of Argead rule in his first book. By referring to Midas, Marsyas would have been able to link his half-brother Antigonus as the contemporary governor of Phrygia not only with the legendary Phrygian king and his legacy, but also with a Macedonian logos attested by Herodotus, creating a connection between Midas and the foundation of Argead rule. According to this logos, there existed old kinship relations between Macedonians and Phrygians who used to dwell at the foot of Mt. Bermium and were called Briges. This tradition was of propagandistic value and could have served to increase the ideological value of Antigonus’satrapy and main base in the rivalry with the other Diadochs.

Catharine C. Lorber

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 53-72

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.005.15775Cultic and other honors offered to rulers by their subjects unambiguously express loyalty to the rulers. Based on data collected for the Seleukid and Ptolemaic empires, a comparison is offered emphasizing the particular qualities of the Seleukid record. The comparison considers geographic distribution, where the honors fell on a public to private spectrum, the occupations and ethnicities of the subjects who offered honors individually, the intensity of these practices, and changes in the patterns over time. We know in advance that honors for the rulers are weakly attested for the Seleukid east, and even in Koile Syria and Phoinike. Should this reticence be interpreted as a possible indication of tepid support for Seleukid rule in these regions? Alternative explanations or contributing factors include preexisting cultural habits, different royal policies, destruction of evidence by wars and natural disasters, and the unevenness of archaeological exploration.

Antonio Invernizzi

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 73-86

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.006.15776The name of Rodogune was not applied only to the well known statuette of Aphrodite Anadyomene from Parthian Nisa, but also to a seal impressed on a sealing from the Nisa Square House. Although the attribution of the seal, unlike that of the statuette, was not discussed in detail, the portrait depicted on it was recognized as that of the Arsacid princess. Actually, the head is not female, but male, and can in all likelihood be that of Apollo with a laurel wreath. The style of execution suggests a relatively late date for the seal, not before the end of the 1st century BC –1st century AD, and allows its impression to be included in the general group of sealings from the Square House of Nisa.

Fabrizio Sinisi

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 87-107

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.007.15777The question of the identity of the issuer of the so-called “Heraios”coinage is analysed, and it is proposed that these series be ascribed to Kujula Kadphises, as already suggested by some scholars. In this regard, the circulation of these coins and the connections established by their imagery are focused upon. Some possible inferences on the original location of Kujula Kadphises are discussed in the concluding part, hypothesizing a southern context different from the northern one commonly ascribed to the founder of the Kushan dynasty.

Achim Lichtenberger, Cornelius Meyer, Torben Schreiber, Mkrtich H. Zardaryan

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 109-125

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.008.15778In March of 2021, the Berlin-based company cmp continued geophysical prospection works at the ancient city of Artashat-Artaxata (Ararat Province, Armenia). The city was founded by Artashes-Artaxias I in the early 2nd century BC and served as his capital. First magnetic measurements were conducted by the Eastern Atlas company in September 2018. In 2021, during the 5-day survey a total surface of approximately 19.5 ha was investigated by use of the LEA MAX magnetic gradiometer array. This system was configured with seven fluxgate gradiometer probes, similar to the system used in the first survey of 2018. The investigated areas of the Eastern Lower City of Artaxata, located to the south of the investigated field of 2018, had good surface conditions with a moderate amount of sources causing disturbance. However, the general level of the magnetic gradient values measured was significantly lower compared to the 2018 data. Despite the lower magnetic field intensity, a continuation of linear structures towards the south was observed. These lines, most likely reflecting streets and pathways, criss-cross the central part of the Eastern Lower City in a NW–SE and NE–SW direction and exhibit partly positive, partly negative magnetic anomalies. Attached to them, some isolated spots with building remains were identified. The negative linear anomalies point to remains of limestone foundations, as detected in the northern part of the Lower City. The low magnetic intensity and fragmentation of the observed structures are most likely due to severe destruction of the ancient layers by 20th-century earthworks for agricultural purposes. Moreover, the southern part of the surveyed area was affected by major changes caused by modern quarries at Hills XI and XII. In general, the results of the two magnetic prospection campaigns greatly aid our understanding of the archaeological situation in the area of the Eastern Lower City of Artaxata, justifying further investigations that will surely contribute to greater contextualization of the identified archaeological structures. The full data sets are also published in open access on Zenodo.

Judean Piracy, Judea and Parthia, and the Roman Annexation of Judea: The Evidence of Pompeius Trogus

Kenneth Atkinson

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 127-145

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.009.15779Pompey the Great’s 63 BCE conquest of the Jewish kingdom known as the Hasmonean State has traditionally been viewed as an inevitable event since the Roman Republic had long desired to annex the Middle Eastern nations. The prevailing consensus is that the Romans captured the Hasmonean state, removed its high-priest kings from power, and made its territory part of the Republic merely through military force. However, Justin’s Epitome of the Philippic Histories of Pompeius Trogus is a neglected source of new information for understanding relations between the Romans and the Jews at this time. Trogus’s brief account of this period alludes to a more specific reason, or at least, circumstance for Pompey’s conquest of Judea. His work contains evidence that the Jews were involved in piracy, of the type the Republic had commissioned Pompey to eradicate. In addition to this activity that adversely affected Roman commercial interests in the Mediterranean, the Jews were also involved with the Seleucid Empire and the Nabatean Arabs, both of whom had dealings with the Parthians. Piracy, coupled with Rome’s antagonism towards the Parthians, negatively impacted the Republic’s attitude towards the Jews. Considering the evidence from Trogus, Roman fears of Jewish piracy and Jewish links to the Republic’s Parthian enemies were not unfounded.

Lucia Visonà

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 147-160

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.010.15780In the Parallel Lives, Aristides and Themistocles are two antithetical characters. This opposition, already present in Herodotus’work and common to the literary tradition of the Persian wars, is particularly emphasized by Plutarch who shapes two characters endowed with opposing character traits who adopt completely different behaviors towards friends or wealth. This profound contrast is intended to highlight the collaboration between the two Athenians, ready to put aside personal differences to devote themselves together to the war against the Persians. The episode of reconciliation is in fact located, unlike other sources (Aristotle, Diodorus), before the battle of Salamis. However, Aristides and Themistocles do not limit themselves to settling their differences : they also take on the role of mediators during the war in order to address the disagreements between Athens and the other Greek cities and avoid hindering the common struggle against the barbarians. To do this, Plutarch adapts some passages of Herodotus (directly or by choosing sources that made such changes) to insert the protagonists of the Lives and create a climate of tension that they can happily resolve. His authorial choices appear consistent with the criticisms against Herodotus in De Herodoti Malignitate. The reflection about the Persian wars in Plutarch’s corpus seems therefore to be animated by a coherent vision, born from the tradition elaborated by the Attic orators in the fourth century : the conflict is seen as a privileged moment of the union between the Greeks, capable of overcoming the almost endemic rivalries that oppose them in view of the common good.

Werner Eck

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 161-169

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.011.15781Several recently discovered lead ingots refer to mining districts in the region of present-day Kosovo. Of particular interest is an ingot with the inscription metallo(rum) Messalini, which refers to M. Valerius Messala Messalinus Corvinus (cos. ord. 3 BC), who was employed as a commander during the Pannonian-Dalmatian uprising of 6–9 AD. He was obviously one of the senators whom Augustus not only honoured with awards for their service, but whom he also supported economically, not unlike Cn. Calpurnius Piso (cos. ord. 7 BC), who had received saltus in Illyricum. These gifts served to create loyalty; but they were precarious gifts because when loyalty ceased, they were reclaimed for the imperial patrimonium.

David M. Jacobson

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 171-196

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.012.15782Without having any contemporaneous account of the Bar Kokhba Revolt comparable to the writings of Josephus that describe the First Jewish Revolt, our knowledge about many aspects of the later uprising is rather sketchy. The publication of Roman military diplomas and the remarkable series of documents recovered from caves in the Judaean Desert, along with other major archaeological findings, has filled in just some of missing details. This study is devoted to a reexamination of the rebel coinage. It has highlighted the importance of the numismatic evidence in helping to elucidate the religious ideology that succoured the rebellion and shaped its leadership.

Oliver Stoll

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 197-217

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.013.15783This article examines defeats and losses as phenomena of an ‘expanded military history’ of Roman History from the Republic to the Principate. It adopts a cultural historical perspective of the military historical phenomenon. “Patterns”and “strategies”are defined, that appear in the sources when dealing with Roman defeats, losses and losers (in particular the commanders or even the emperor himself). Above, the historiography of the Roman imperial period is exemplary examined to see what reasons, interpretations or explanations are given there for suffering a defeat and whether and how these are part of narrative strategies. Sometimes military catastrophes simply were concealed, belittled or reinterpreted. How Rome dealt with defeat tells something about Rome’s society and especially the elite: “Roman culture”or “Rome’s political culture” shaped the way how the military phenomenon of defeat was dealt with. Defeats could also be seen as chances for future victories, they were good for learning and examples for withstanding with the help of morale and disciplina. In the end Rome’s strategies in dealing with such catastrophic events of ‘military history’overall seem to paint the picture of Rome as a resilient socio-political and military system!

Aleksandra Kubiak-Schneider, Achim Lichtenberger

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 219-236

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.014.15784The finds from the ancient city of Gerasa brought in 1930’two inscriptions dated to the second half of the 1st century CE which mention the deity called Pakeidas. The aim of this paper is to discuss Pakeidas and his relation to another god labelled Theos Arabikos worshipped in the same city. The authors make a broad Semitic overview on the etymology of the name Pakeidas looking at the West and East (Akkadian) Semitic evidence. The authors discuss the possible location of the temple dedicated to this god beneath the Cathedral. They also reexamine in the light of epigraphic sources in comparison to the Aramaic material from the Near East the function of archibomistai, cultic agents who served to this local god.

Peter Franz Mittag

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 237-247

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.015.15785Especially in regard to the multitude of depictions on coins and medallions referring to the history of Rome in the early 140s, the omission of corresponding depictions in the year 147/148, when Rome’s birthday was celebrated for the 900th time, is remarkable. Instead of referring to this important event, the coins and medallions of Antoninus Pius present themselves entirely under the sign of his decennalia. Apparently, the reference to the anniversary of the reign was considered more important than Rome’s birthday. Reasons for this decision could have been problems of acceptance, which are only hinted at in the literary sources, which are consistently friendly to Antoninus.

Giusto Traina

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 249-259

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.016.15786Some evidence points at the presence of Orientals in late Roman Italy: traders (labelled “Syrians”), petty sellers (the pantapolae in Nov. Val. 5), but also students, professors such as Ammianus Marcellinus, or pilgrims. Although being Roman citizens, nonetheless they were considered foreign individuals, subject to special restrictions. The actual strangers made a different case, especially the Persians. The situation of foreign individuals was quite different. Chauvinistic attitudes are widely attested, and they worsened in critical periods, for example after Adrianople. This may explain the laws of early 397 and June 399, promulgated during Stilicho’s regency, which prohibited the wearing of trousers (bracae) and some fashionable boots called tzangae. Of course, some protégés of the imperial court had the right to enter Italy, as it was the case of the Sassanian prince Hormisdas, who accompanied Constantius II in his visit of Rome in 357.

Simone Rendina

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 261-266

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.017.15787In Themistius’orations there are many clear and direct references to the Greek literature of the 5th and 4th centuries BCE. However, there are also more subtle references to these classical texts. In this paper, two references to classical Greek historiography are identified in Themistius’Oration 18. As we shall see, in order to praise the refashioning of Constantinople by Theodosius the Great, Themistius subtly quoted a passage by Xenophon. In order to highlight the splendour of the city of Constantinople, he also used as a reference one of the most eminent classical encomia of cities, that is, Pericles’funeral oration from the second book of Thucydides’ History. Both references served to enhance Themistius’already good relations with Theodosius I, who had recently renovated Constantinople with new monuments. This research thus stresses the relevance of quotations in Themistius’orations when studying his political agenda, including quotations that are less obvious and less easily identifiable.

Touraj Daryaee

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 267-284

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.018.15788This essay discusses the importance of Ctesiphon in the historical and literary tradition of Sasanian and Post-Sasanian Iran. It is proposed that there was a significant buildup of the Ctesiphon’s defenses in the third century that it made its conquest by the Roman Empire impossible and its gave it an aura of impregnability. By the last Sasanian period the city was not only inhabited by Iranian speaking people and a capital, but it also became part of Iranian lore and tradition, tied to mythical Iranian culture-heroes and kings. Even with the fall of the Sasanian Empire, in Arabic and Persian poetry the grandeur and memory of Ctesiphon was preserved as part of memory of the great empires of the past.

Michael Whitby

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 285-300

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.019.15789The homily on the Avar siege of Constantinople in 626 attributed to Theodore Syncellus shares numerous linguistic features both with Theodore’s homily of 623 on the Virgin’s Robe and with George of Pisidia’s poem of 626/7 on the siege. Theodore and George both celebrate the combined efforts of Patriarch Sergius and the Virgin Mary in saving the city, but Theodore also highlights the involvement of other agents, in particular the patrician Bonus and the young Heraclius Constantine, who were jointly in charge of the city while Emperor Heraclius was campaigning against the Persians. The homily is structured around the exegesis of three Old Testament passages: the promise in Isaiah 7 to King Ahaz about the salvation of Jerusalem; the analysis of numbers in Zachariah 8.19; and God’s destruction of Gog and Magog in Ezekiel 38–39.

Simon James

ELECTRUM, Volume 29, 2022, pp. 301-328

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.22.029.16524The centenary of the establishment of the Department of Classics at the University of Kraków coincides with that of the beginnings of the study of the ‘Pompeii of the Syrian Desert.’In spring 1920, British Indian soldiers digging in the ruins known as Salihiyeh overlooking the Euphrates accidentally revealed ancient paintings. Recorded by archaeologist James Henry Breasted, these discoveries would soon lead to further excavations by Franz Cumont (1922–1923), and eventually to the great Yale-French Academy expedition under Mikhail Rostovtzeff (1928–1937). By then the site was famous as ‘Dura-Europos,’giving us remarkable insights into Hellenistic Greek, Parthian, Roman, early Christian and Jewish life in the Middle East. Not the least of the discoveries related to the soldiers of Dura’s Roman garrison. This paper traces the history of the revelation—and, in part, invention—of Dura-Europos in the 1920s. It is a story of eminent scholars, but also of others who actually revealed the evidence: soldiers, both officers and men, of the armies of the British and French empires which dominated the region at the time. Today, at a time of ‘decolonisation’of scholarship, the very formulation ‘Dura-Europos’itself is a subject of contention.

Publication date: 02.07.2021

Editor-in-Chief: Edward Dąbrowa

Cover photography: Cover photography: Tigranokert. A clay disc with Armenian inscriptions from the excavations of the Large Church

The publication of this volume was financed by the Jagiellonian University in Krakow – Faculty of History.

Edward Dąbrowa, Giusto Traina

ELECTRUM, Volume 28, 2021, pp. 7-8

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.21.001.13359Achim Lichtenberger, Giusto Traina

ELECTRUM, Volume 28, 2021, pp. 11-12

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.21.002.13360Giusto Traina

ELECTRUM, Volume 28, 2021, pp. 13-20

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.21.003.13361The history of the kingdom of Greater Armenia (after 188 BCE–428 CE) has been generally interpreted from two different standpoints, an ‘inner’ and an ‘outer’ one. Greater Armenia as a marginal entity or a sidekick of Rome during the endless war with Iran, and even Iranian scholars neglected or diminished the role of Armenia in the balance of power. This paper discussed some methodological issues.

Klaus Geus

ELECTRUM, Volume 28, 2021, pp. 21-40

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.21.004.13362Ptolemyʾs Geographike Hyphegesis (Introduction to Geography) (ca. AD 150) consists of a huge and invaluable stock of topographical information. More than 6,000 toponyms are even defined by coordinates. Nevertheless, Ptolemyʾs cities are often misplaced or pop up more than once in his maps. This is especially true with his confusing description of Armenia (geogr. 5.13), which caused a modern scholar to call it a ‘parody’ of his work and method. This paper aims at clarifying the basic error in all of Ptolemyʾs coordinates and proposes some explanations and corrections for his Armenian toponyms.

Edward Dąbrowa

ELECTRUM, Volume 28, 2021, pp. 41-57

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.21.005.13363The aim of this paper is to present Parthian-Armenian relations from the end of the 2nd century BCE to the so-called Treaty of Rhandeia (63 CE). This covers the period from the first contact of both states to the final conclusion of long-drawn-out military conflicts over Armenia between the Arsacids ruling the Parthian Empire and Rome. The author discusses reasons for the Parthian involvement in Armenia during the rule of Mithradates II and various efforts of the Arsacids to win control over this area. He also identifies three phases of their politics towards Armenia in the discussed period.

Touraj Daryaee

ELECTRUM, Volume 28, 2021, pp. 59-67

https://doi.org/10.4467/20800909EL.21.006.13364This paper discusses the idea of Armenian and Iranian identity in 3rd century CE. It is proposed that the bordering region of the Armeno-Iranian world, such as that of the Siwnik‘ and its house saw matters very differently from that of the Armenian kingdom. The Sasanians in return had a vastly different view of Armenia and Georgia as political entities, and used their differences to the benefit of their empire.

Carlo G. Cereti

ELECTRUM, Volume 28, 2021, pp. 69-87